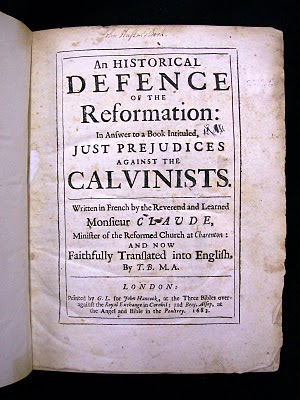

Recently, I looked at one of Claude’s earlier publications, pictured above. An Historical Defence of the Reformation is the English translation of Claude’s Défense de la Réformation (1682). The translation was made by “T.B. and M.A.” and was printed by “G.L.” in 1683.

Larkin! – George Larkin was one of London’s notorious underground printers who defied the Crown's oppressive censorship of the English press in late 1600s. Loosely connected with the Baptists, Larkin started his outlaw adventures in 1666, printing no less than the first edition of John Bunyan’s Grace Abounding, an anti-clerical work by Ralph Wallis, and some satirical poems by Andrew Marvell. That’s a pretty formidable introduction to the book trade.

After narrowly escaping out the back door during a house search sanctioned by the Stationer’s Company in 1668, Larkin turned informant, ratting-out his fellow radical printers John Darby and Nathan Brookes to Sir Roger L’Estrange, overseer of the publishing trade by appointment of the Restoration court (and no stranger to publishing controversy in his own right). Even this alliance couldn’t keep Larkin out of harm’s way; his printing career was punctuated by surprise searches, fines and periods of imprisonment.

Back to this book. The type used by Larkin displays many of the same early-Baroque elements of those used in Mather’s A Sermon (printed at Boston in 1685) and D’Anvers’ A Treatise of Baptism (printed at London in 1674) which I discussed in earlier posts (See Older Posts).

One of the interesting attributes of this particular page is the way in which the sidenote is butted directly up against the main textblock with only a thin lead between them. However, in the upper right-hand margin you can see from the ghost of the note printed on the verso of this page that it is set with ample space between it and the main textblock. Notice the dagger used to mark the note in the main text (eleven lines down from the top) and that its form is slightly different than the dagger of the smaller-sized font used for the sidenote itself.

This font includes a number of ligatures, or single pieces of type which combine and link two or more letters. In modern digital fonts, ligatures for the combinations ‘fi’ and ‘fl’ are standard issue, but an extended pallet of ligatures for further f combinations (ff, ffi, ffl, fj, fb, etc.) and historical ‘discretionary ligatures’ or ‘quaints’ (ct, st, is, us) are often included with Opentypes fonts with extended character sets.

Speaking of discretionary, notice that one line uses the italic ligature for ‘us’ on two words, but not on the third. Is this simply an oversight on the part of the compositor?

Not only does the ligature save the compositor time, allowing him to set two letters while only reaching out to one compartment in the case, the single glyph is slightly more compressed than the combination of the single sorts ‘u’ and ‘s’, saving space. It’s also very beautiful.

ANDREW STEEVES ¶ PRINTER & PUBLISHER