It helps to know where to look, however, and since the sociological side of literature and research interests me as much as books themselves, many of my bibliographic adventures begin with cruising the library’s re-shelving carts. When I go into an archives, I want to know what other people are curious about and see what items were recently requested for viewing. It’s a bit like looking for salamanders, though. You can turn over a lot of rocks before you find anything interesting.

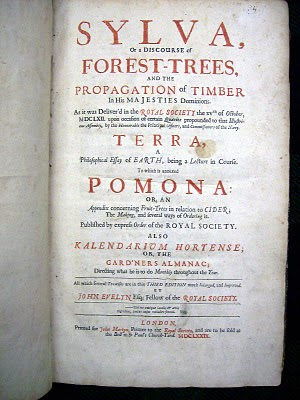

Recently, at the bottom of a stack of more contemporary books, I spied a battered copy of the third edition of Sylva, or, A Discourse of Forest-Trees, and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesties Dominions (1679) written by the English horticulturist and diarist John Evelyn (1620– 1706). I wonder who had been looking at it, and why?

I knew of this book from Thoreau, who refers to it briefly in Walden and mentions it again at greater length in his journal a few years later. On 6 June 1852 Thoreau comments:

Evelyn has collected the fine exaggerations of antiquity respecting the virtues and habits of trees and added some himself.[…] If the oft-repeated glorification of the forest from age to age smacks of religion, is even druidical, Evelyn is as good as several old druids, and his “Silva” is a new kind of prayerbook, a glorifying of the trees and enjoying them forever, which was the chief end of his life.

Evelyn’s Sylva is a practical guide to arboriculture intended to improve the understanding and practice of forestry. It was first published as a paper presented to the newly constituted Royal Society in 1662. This third edition was printed for the noteworthy London bookseller and publisher John Martyn (d. 1680), whose shop was located in St. Paul’s Churchyard under the sign of the bell. Martyn, in partnership with John Allestry, had acquired the lucrative monopoly as printer to the Royal Society in 1663.

A couple of different text types were used in Sylva. The two types used in the pages reproduced above, while similar in structure, are quite different. Most obviously, the first one has a more lively italic which makes liberal use of swash capitals.

In the days of handcut punches, each size the punchcutter cut was essentially a variation on a theme as he made countless little refinements and alterations in order to achieve the best visual result at each size. One such variations is clearly seen when these two roman types are scaled to the same x-height and similar words are set side by side. Note how the extenders are taller on the first type than on the second. Types cut for smaller sizes tended to have shorter extenders, even when the structure of the letters was otherwise similar.

Whatever Thoreau made of Evelyn as a botanist, he certainly found Sylva fertile ground as a work of literature. Her wrote in his journal on 23 March 1953:

Evelyn and others wrote when the language, was in a tender, nascent state and could be moulded to express the shades of meaning; when sesquipedalian words, long since cut and apparently dried and drawn to mill, – not yet to the dictionary lumber-yard, – put forth a fringe of green sprouts here and there along in the angles of their rugged bark, their very bulk insuring some sap remaining; some florid suckers they sustain at least. Which cords, split into shingles and laths, will supply poets for ages to come.

ANDREW STEEVES ¶ PRINTER & PUBLISHER

No comments:

Post a Comment